The scene was hushed with concentration. Eleven scientists and Northwest Trek staff members bent over rows of tables outside the Northwest Trek conservation center, far outside the public area at the Eatonville wildlife park. Birds chirped in the surrounding forest. But the real stars of the intense scientific focus were some 350 northern leopard frogs – most of whom were sleeping soundly under anesthetic.

It was tagging and measuring day, an effort involving three different partner organizations, in careful preparation for releasing these endangered frogs back into the wild of eastern Washington. The goal? To help repopulate a vanishing species.

First, Catch Your Frogs

“So many frogs!” “We’re almost done.”

It was 7:30 a.m., and three green shirted figures were bent double over a big black tub of water.

Northwest Trek zoological curator Marc Heinzman and keepers Jessica and Miranda, each armed with a net, were scooping out the last of over 350 northern leopard frogs and gently depositing them into blue tubs. The frogs had been growing for the last few months at the Northwest Trek conservation center, raised from egg masses that had been collected in May by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW).

Due to habitat loss, disease, pollution, climate change and invasive predators like bullfrogs, northern leopard frogs have seen a serious decline throughout the western U.S. and Canada. Now, there’s just one place in Washington where they’re found: the Potholes Reservoir in the Columbia Basin Wildlife Area.

In a pilot project in 2019, egg masses from that habitat area were collected by WDFW and raised by Oregon Zoo for re-release when the frogs had grown old enough to survive on their own.

Paused in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the project was now happening again – this time at Northwest Trek as well. Funded by a US Fish and Wildlife Service grant, the project brings together the Fish and Wildlife Service, WDFW, Washington State University (WSU), Northwest Trek and Oregon Zoo.

And tomorrow, the frogs would be taken out to their home habitat at the Potholes Reservoir to be released into the wild.

“Giving these frogs a headstart by raising them free of predators gives their whole population a better chance of survival,” says Heinzman. “We’re thrilled to be able to help with that.”

Finally, all frogs had been lifted into the blue tubs, and the keepers carried them over to the under-cover work stations. Two rows of tables were set up for the various stages of the process of weighing, measuring and tagging the frogs for later identification by researchers at both WDFW and WSU.

Tiny Dots on Tiny Frogs

As everyone assembled to their stations, the team leaders conferred on how best to coordinate a delicate process involving hundreds of rare frogs. Emily Grabowsky, WDFW biologist, and Dr. Erica Crespi, associate professor of biology at WSU and lead researcher on the project, share tips they learned during the tagging of another 100-plus leopard frogs raised at Oregon Zoo and released two weeks ago at the Potholes Reservoir site.

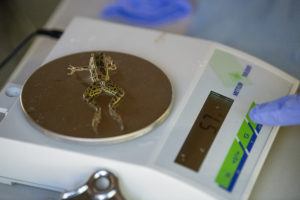

Dr. Allison Case, head veterinarian at Northwest Trek, weighed in with years of expertise in anesthetizing amphibians, and lent the scientists a pair of illuminated magnifying glasses and a headlamp, to better work with the frogs’ tiny legs. Keeper Rebecca and conservation coordinator Rachael set up a scale, ruler and data spreadsheet, while Dr. Colin Berg, intern veterinarian from sister zoo Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium, manned the recovery tubs.

Veterinary technician Tracy Cramer and Marc Heinzman assisted, along with Lex Dulmage, a WSU graduate student in the Crespi Lab.

“Are we ready?” called Dr. Case. “Okay.”

With practiced care, keeper Jessica began lifting frogs one by one into the shallow lidded tubs of anesthetic bath. As each frog stopped hopping and lay quite still, Dr. Case scooped them out and transferred them carefully to where Dr. Crespi, Emily Grabowsky and Lex Dulmage were waiting with tiny syringes full of fluorescent green elastomer tagging substance. (The elastomer is nonharmful, and allows later identification in the wild.)

“Here, watch,” Dr. Crespi instructed her student.

Turning the first frog on its back, she delicately inserted the needle just above a tiny ankle. She rolled one bead of the elastomer into the leg, then sealed the skin. Laying the frog on a single sterile glove, she carried it over to the weighing table, where keeper Rebecca weighed it (4.2 grams) and measured on a small ruler (a tiny 10 mm). As Rachael noted the measurements, Rebecca lifted the little green-and-brown frog into one of four fresh-water recovery tubs, where Dr. Berg began monitoring for signs of recovery.

Partners in Frog Action

As frog after frog was anesthetized and transferred, Grabowsky, Dulmage and Dr. Crespi focused intently, skillfully tagging each frog’s left leg with the neon dye.

“We do the underside, because it’s a little easier to see and gets less wear in the wild,” Dr. Crespi explained. A stress physiologist and ecologist, Dr. Crespi has spent decades researching behavioral response in amphibians to environmental factors like habitat or stress. Her role in the northern leopard frog project isn’t just as an expert tagger of hundreds of amphibians: She’s also learning what makes frogs more likely to survive in the wild, based on how they react to stimuli. She’ll be there tomorrow at the Potholes Reservoir ponds release, and five days later as well to watch their stress response.

But the release process starts much earlier, with Grabowsky and her WDFW team preparing the habitat site weeks beforehand.

“These frogs can only hunt and survive when the vegetation is at around 20 percent coverage,” Grabowsky explains. “So we manage that by using prescribed fire, manual clearing and some spot herbicide for invasive plant species like cattails and common reed.”

Then there’s the bullfrog problem: An invasive species, bullfrogs are both competitors and predators of northern leopard frogs, and one of the big reasons why these egg masses were given a headstart through the tadpole phase. Some manual removal can be done at some of the hundreds of ponds where the frogs live, but the most effective remedy is building up the frog population – exactly what this project aims to do.

Finally, Grabowsky will help the new frogs along by releasing them at their Potholes habitat inside a large net, some 40×40 feet in area and four feet high. They’ll stay there for the first week, learning how to hunt insects without human intervention.

Then they’re on their own – with just one telltale green dot on one foot (and a different color dot for the Oregon Zoo frogs) so scientists can spot them in future to determine the success of the project.

Frog After Frog

Back at the conservation center, the action is speeding up. The frogs are moving through the work stations in a steady, efficient flow, with communications ringing out around the space.

“How’s the recovery going?” calls Dr. Case from the anesthetic baths.

“Getting faster,” calls back Dr. Berg, as he lifts out another frog. He’s watching for vital signs: throat breathing (frogs just breathe through their skin when asleep), pushing up, response to stimuli, flipping over when turned on their backs. As each frog starts swimming again, keeper Rebecca lifts it out and into the transport tubs lined with damp towels, ready to go tomorrow to the Potholes.

“This is a tremendously healthy group, with expert care,” says Dr. Case. “I have good expectations for their survival.”

“Come back, little friend,” says Jessica, catching a frog just as it wriggles out of her hand onto the table.

Nearby, Dr. Crespi’s team don fresh pairs of sterile gloves to swab frogs: The swabs will go to a WSU pathology lab to test for chytrid, a fungus that’s having a deadly impact on frogs all over the country.

“Wow, 10.1 grams!” calls out Rachael from the weigh station.

“Ooh, that’s big!” replies someone.

“This is so exciting,” murmurs Rebecca, tenderly measuring a tiny frog.

With weights between 2.5 and 10.2 grams and nose-to-bottom lengths between 31-50 mm, the frogs are petite, with little leopard spots up and down their backs and long springy legs. Keepers will feed them some crickets tomorrow after they’ve recovered from the anesthetic, and the three-hour journey will be done in the afternoon, to time the release for the cool of dusk.

After that, it’s up to these energetic little amphibians to hunt, avoid predators, lay eggs and grow their species – helped along by frog-raising humans over the next few years of the project.

Frog Future

Is it helping?

“It’s too soon to tell,” says Grabowsky, waiting to tag her next frog. “So far we haven’t counted any from the first year of the project. But we’re hoping to see more and more in the future. Leopard frogs are an important indicator of water quality, they are both predator and prey, and frogs are often children’s first experience with wildlife. If we can improve and conserve wetland habitat that is good for frogs, we will also benefit other species as well.”

“An ecosystem is like a jigsaw puzzle,” sums up Heinzman. “You need all the pieces there to make a strong, healthy whole.”